-

Lincoln Visits Dubuque

When I first published versions of this article in two magazines back around 2008, I relied on scant and inaccurate accounts. Thanks to a recent two-part article by John T. Pregler in the Iowa History Journal (“Locating Lincoln: Research confirms rumored trip to Dubuque in 1859,” March/April and May/June, 2021), I have been able to update, correct and vastly improve my version. Many thanks to Mr. Pregler.

Just a year and a half before he would be elected president, Abraham Lincoln visited Dubuque, Iowa, in first-class style. The one-time prairie lawyer had undergone an impressive transformation, mirroring the growth of his home state of Illinois.

The man who had grown up in log cabins was a big noise in the Republican Party by this time, having run for U.S. Senate in 1858 against perennial presidential contender Stephen A. Douglas. Lincoln carried the popular vote, but the incumbent Douglas won, because the state’s legislative districts were not proportionally balanced at the time. Democrats won a majority in the legislature, and prior to 1914 it was state legislatures that chose U.S. senators.

The senatorial race received nationwide coverage, which largely focused on the seven debates between the two held from August through October. Lincoln’s debate oratory put him on the road to the White House, although he wasn’t seriously considered as a presidential candidate until after his Cooper Union speech in New York in February, 1860.

At the time of his Dubuque visit in 1859, Lincoln was a popular political speaker on a mainly regional basis who still needed to work his day job to provide for his family. As he said of his public speaking in a letter to Hawkins Taylor of Keokuk later in the year, “I am constantly receiving invitations which I am compelled to decline.” He couldn’t afford to accept them. “It is bad to be poor–” he stated somewhat exaggeratedly, “I shall go to the wall for bread and meat if I neglect my business this year as well as last.”

His business was lawyering, and he had for several years been in the front rank of that profession in Illinois. Lincoln continued to take on local cases riding circuit in the state’s Eighth Judicial District until the year he was elected president, 1860. However, he was by now a highly respected attorney frequently in the hire of the railroad companies, which deserve much of the credit both for Lincoln’s relative prosperity and for the phenomenal growth in Illinois’s population and economy. Lincoln received an annual $250 retainer and a free railroad pass from the Illinois Central Railroad, which kept employing him even after he sued them to collect a then-enormous $5,000 fee for its case against McLean County, Illinois.

This is a story I will recount in oppressive detail after I’m done talking about Lincoln’s Iowa connections and run a series on Lincoln’s legal career. For now, here is a briefer version to explain what Lincoln was doing in Dubuque. McLean County (home of Bloomington) attempted in 1853 to assess for taxation the ICRR property within its boundaries. The railroad pointed to its charter from the state, which set a level of state tax that it must eventually pay but also said it would be exempt from local property taxes. The county said that the legislature couldn’t void the county’s right, established in the Illinois constitution, to tax all property.

Lincoln and ICRR attorney James Joy tried the case all the way to the Illinois Supreme Court. The case was so complicated that it was in fact tried there twice. The high court finally ruled in the railroad’s favor in 1856. But when Lincoln presented his bill for $2000, the railroad balked. Lincoln felt he had saved the railroad at least $500,000, considering that other counties would have followed McLean’s lead had it succeeded, so he doubled down, in a manner of speaking. Actually he doubled-and-a-half down, raising his fee to $5000 and taking his employer to court in 1857. At first Lincoln feared that his retainer was at an end, but ICRR officials reconsidered their position and decided not to contest the suit. Why? The railroad men realized they were facing related litigation from the state, and didn’t think they could afford to have a lawyer who had familiarized himself with their finances from the inside for three years representing their new opponent. Explaining it later to the company president, the railroad’s chief attorney said, “We can now look back & in some degree estimate the narrow escape we have made.”

The problem had switched from county taxes to state taxes, from which the railroad had a six-year exemption written into its charter. But the six years had passed, and the railroad still couldn’t afford to pay the tax based on the valuation that State Auditor of Public Accounts Jesse Dubois had fixed on the ICRR’s property. Once back at the controls, Lincoln masterfully manipulated a number of levers over the next two years and won for the railroad everything it desired. In July of 1859 Auditor Dubois (a close political ally of Lincoln’s, in case anyone thinks that mattered (it did)) undertook the annual visual assessment of the railroad’s entire property, including all 705 miles of rail. Given that Dubois’s method of assessment was in dispute by the railway, the ICRR organized a nine-day journey in which Dubois was accompanied by state officials, a member of the railroad board of directors, and legal counsel for both sides. Lincoln was there as attorney for the railroad, while Stephen Logan advised the state. Logan had been the second prominent attorney to make Lincoln a partner, back in 1841.

This official tour took on the aspect of a pleasure excursion as the party was filled out with wives and children of several of the travelers. Dubois, Lincoln and Logan were accompanied by their families, as was former state auditor Thomas Campbell. The railroad furnished a locomotive and a private car for the group, which left Springfield on July 14 in weather that often exceeded 100 degrees. After two days of viewing rails, rolling stock and buildings, they reached the northern terminus of the Illinois Central line in Dunleith, Illinois, on the banks of the Mississippi. The reason for their next travel leg is open to speculation. What we know for sure is that the party then boarded a ferry bound for Dubuque, Iowa.

There was no bridge at that time between Dubuque and Dunleith, which is now known as East Dubuque, but a proposal for one existed, because the Illinois Central had plans to connect up with Dubuque and lay track to the next intervening ocean. By 1859, the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad, which had been incorporated in 1853 by officials of ICRR, was building the line between Dubuque and Dyersville. Roswell B. Mason, who had been engineer-in-chief of the ICRR, moved to Dubuque to be chief engineer of the D&PRR. He was also slated to be the engineer for the Dunleith to Dubuque bridge, which was delayed by the Panic of 1857. This economic downturn forced a number of railroads into bankruptcy, and then the Civil War intervened, so that the bridge was not completed until 1869.

Meanwhile, Mason left his chief engineer positions to partner in a local firm, Mason, Bishop and Co., that contracted with the railroad to build the line to Dyersville. It is likely that Lincoln crossed the Mississippi to confer with Mason and with Benjamin Provoost, who had succeeded Mason as chief engineer of the Dubuque & Pacific. The two-day sojourn in Dubuque was the longest stop on the trip.

The group took lodgings in the recently expanded and modernized Julien House hotel, which stood four blocks from the Julien Theatre, a building housing offices for both Mason, Bishop and Co. and the Dubuque & Pacific Railroad. Lincoln was quite familiar with Mason. Remember Lincoln’s 1857 trial, Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge Company, concerning the steamboat that collided with the Rock Island-to-Davenport bridge? Mason was on the stand for two days in that trial, testifying for the defense about his experience in designing this bridge and others to take river currents into account for safe steamboat navigation. More to the point, Mason would be one of three key witnesses that Lincoln would call to testify four months after the visit to Dubuque in People v. Illinois Central Railroad, where the Illinois Supreme Court would disagree with Jesse Dubois’s taxable valuation of the property and side with the railroad.

It would be reasonable to assume that Lincoln wished to strategize with Mason and Provoost on the complex issues relating to the railroad’s taxes. (Another court case, relating to back taxes, would not be resolved until early 1860.) But it seems odd that state officials would be along for the ride, traveling in the same ICRR train, staying in the same Dubuque hotel, all palsy-walsy with the railroad folks they were suing. As I said earlier, I will describe this case in greater depth in another context, but until then I will let you ruminate on the fact that fellow travelers attorney Logan, State Auditor Dubois, Secretary of State Ozias Hatch and State Treasurer William Butler were all personal friends and political supporters of Lincoln, the attorney for the company they were suing.

Lincoln’s presence in Dubuque did not go unnoticed. His leadership role in Republican politics made him a noteworthy visitor, and the Dubuque Herald reported on July 19, “Hon. Abram Lincoln, of Illinois, is in town and is stopping at the Julien House.” Story to follow? No, that was all of it. Although the newspaper didn’t seem particularly excited, some local Republicans were. Young attorney William Boyd Allison, who was a few years from beginning his career as one of Iowa’s most prominent and longest serving U.S. representatives and senators, joined some other Republican enthusiasts in traipsing over to the Julien House to hopefully catch sight of Senator Douglas’s noted antagonist. Allison later said, “When I heard he was in town, I went to the hotel to see him. However, I didn’t feel important enough to make his acquaintance.” The two would become acquainted later when Allison was elected to Congress in 1862.

On the morning of the 18th the crowd from Illinois ferried back to Dunleith and again boarded the special train and headed to Chicago, where the Chicago Tribune was a bit less mysterious about Lincoln’s comings and goings. An article in the July 20 edition entitled “Assessment of the Illinois Central Road” identified Auditor Dubois’s bounden duty and elaborated on his traveling companions. He was “accompanied by Hon. O.M. Hatch, Secretary of State, Hon. A. Lincoln, W.H. Butler, Esq., T.H. Campbell, late Auditor, Hon. S.T. Logan, together with several ladies,” and they were “en route from Dunleith to Cairo” in far southern Illinois. “A car and locomotive were put at the disposal of the party at Springfield, and they are making a pleasant but rather warm trip.”

The group arrived back in Springfield late on July 22. The case went to trial in November, the judge found for the railroad, the case for the back taxes came up in January, Lincoln won again, the railroad paid him $500. There are details, perhaps very telling details, that I am not aware of that explain why he fought for $5000 from the railroad in Illinois Central RR v. McLean County and accepted only $500 in People v. Illinois Central Railroad, a case of similar length and complexity. I am left in doubt and perplexity.

Let’s end with postscripts that we can provide more definitively. Roswell Mason, engineer-in-chief for multiple railroad and bridge projects and Dubuque resident at the time of Lincoln’s visit there, moved to Chicago in 1865 to help engineer the cattywampusing of the Chicago River so that it would flow away from instead of into Lake Michigan. In 1869 Mason was elected mayor of Chicago. The Great Fire of 1871 took place near the end of his term, and he was credited with swift steps that helped Chicago rise from the ashes to become America’s Second City. The Illinois Central eventually expanded into Iowa, leasing the Dubuque and Sioux City road from Dubuque to Iowa Falls in 1867, and reaching Sioux City in 1870. The Julien House was expanded again after the Civil War, but the building burned down in 1913. The present Julien Inn stands on the same site at Second and Main Streets.

Julien House, Dubuque, ca. 1859 -

Lincoln’s Burlington Visit

Lincoln’s legal practice saw steady growth, while his political career advanced by fits and starts. After an unsuccessful run for one of Illinois’s U.S. Senate seats in 1854-55, he stood for the other in 1858. In October of that year he went to Burlington, Iowa to give a speech. There may not have been many voters in Burlington who could help him, but he had a number of reasons to make such a visit.

One reason was the doggedness of Burlington residents over the years in inviting Lincoln to come. He had turned down invitations in 1844, 1856 and 1857 that we know of. Burlington was a small settlement at the time, but it had served as the second capital of the Wisconsin Territory in 1837 and was from 1838 to1840 the capital of the Iowa Territory after it separated from Wisconsin. Thus, it was an important political center in the state, and it was the home of James W. Grimes. A member of the first territorial legislature at Burlington who was elected governor in 1854, Grimes authored at least two of the requests for Lincoln visits.

Lincoln explained his disinclination to visit in 1856 in his reply to Grimes: “1. I can hardly spare the time. 2. I am superstitious. I have scarcely known a party preceding an election to call in help from the neighboring States, but they lost the State.”

When Grimes invited him again in 1857, Lincoln wrote that he was very anxious for Republican success in Iowa’s 1858 congressional elections but “I lost nearly all the working-part of last year, giving my time to the canvass; and I am altogether too poor to lose two years together.”

When 1858 came around, Lincoln was trying to fulfill his life dream of election to the U.S. Senate. His opponent was the Democratic incumbent, Stephen A. Douglas, whose Kansas-Nebraska Bill of 1854, which gave new states the right to vote on allowing human bondage, had electrified the slavery issue and brought Lincoln out of self-imposed political exile.

Lincoln proposed a series of debates, and Douglas agreed to hold seven. The fifth was scheduled for October 7 in Galesburg, about 46 miles east of Burlington. They would follow that debate with one down the Mississippi River in Quincy on October 13. Des Moines County Republican Chairman Charles Darwin reasoned that Burlington wouldn’t be out of Lincoln’s way, so he sent him an invitation to speak.

(You probably didn’t mistake Burlington’s Charles Darwin for the British evolutionist of the same name, but this coincidence gives us a chance to note another coincidence: The evolutionist Darwin and Lincoln share the same birthday, February 12, 1809.)

Another factor influenced Lincoln’s acceptance of Darwin’s request. Part of Lincoln’s electoral strategy was to speak in a town after Douglas had spoken there so that he could answer Douglas’s points, and Douglas had already agreed to talk in Burlington. Consequently, after a 1 pm speech in Oquawka, Illinois on Saturday, October 9, Lincoln immediately embarked on the Rock Island packet to sail twenty miles downriver to address an Iowa crowd in Burlington that evening. The staunchly Republican Burlington Hawk-Eye had given details of the impending visit in its October 8th edition, and wound up by saying of Lincoln, “He says he has got so used to speaking that it don’t hurt him a bit and he will talk as long as we want to hear him! HUZZA FOR LINCOLN!”

On his arrival, Lincoln checked in at the Barrett House to freshen up before his speech. Years later, eyewitnesses at the hotel recalled instances of Lincoln’s simplicity. On arrival, he handed the clerk a small packet wrapped in newspaper and said, “Please take good care of that. It is my boiled shirt. I will need it this afternoon.” Apparently it was the sum total of his luggage.

Later, the editor of the Hawk-Eye saw him putting the shirt on. Clark Dunham said that Lincoln came down the stairs to meet a local delegation with his arms stretched high as he struggled to pull his white shirt over his head. He finished tucking his shirttails into his trousers just as he reached the group.

What Dunham did after meeting Lincoln at the hotel is something of a mystery, because his October 11 newspaper reporting on the speech stated, “We regret exceedingly that it is not in our power to report his speech in full this morning.” No transcript of the oration has yet been uncovered. The Hawk-Eye was somehow able to describe the speech as “a logical discourse, replete with sound argument, clear, concise and vigorous, earnest, impassioned and eloquent.” It estimated the crowd at “twelve to fifteen hundred ladies and gentlemen.” Lincoln spoke for two hours, and it apparently “didn’t hurt him a bit”: the newspaper reported (perhaps with a touch of bias) that Lincoln “appeared Saturday evening fresh and vigorous, there was nothing in his voice, manner or appearance to show the arduous labors of the last two months.” This in contrast to Douglas, “whose voice is cracked and husky, temper soured and general appearance denoting exhaustion.”

The speech was given at Grimes House, a hall owned by Governor Grimes. After spending the night at the Barrett House, Lincoln visited Grimes at his home on Sunday before leaving town. Presumably, Lincoln devoted at least a portion of his Saturday speech to politicking for Grimes, who, like Lincoln, was running for the Senate. Unlike Lincoln, he was successful.

The loss was disappointing to Lincoln, but Grime’s biographer, William Salter, who heard both Lincoln and Douglas speak in Burlington, put it in perspective. “Had Mr. Lincoln been elected senator,” he wrote, “in all probability he would never have become President.” And his visit to Burlington would likely have been forgotten.

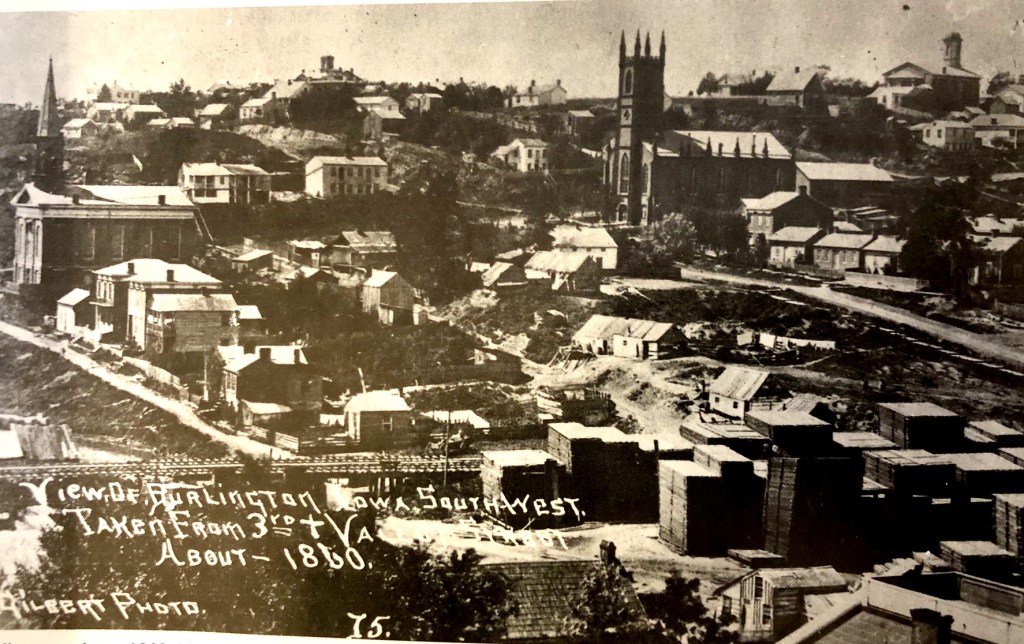

Burlington in 1860 -

Abraham Lincoln and the Case of the First Mississippi River Bridge

by Grant Veeder

Lincoln was a natural public speaker whose abilities to clearly explain difficult concepts and to emotionally sway his listeners formed a strong underpinning to his successful legal career. The wide respect for his reputation led to his involvement in a lawsuit that had a dramatic effect on Iowa’s early growth.

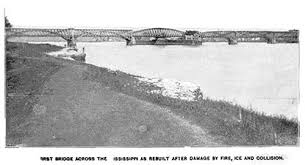

The first bridge across the Mississippi River, three years in the building and completed in 1856, connected Rock Island, Illinois and Davenport, Iowa, and was a major breakthrough for western travel and commerce. Riverboat operators previously had a monopoly on the large-scale movement of passengers and goods, and had tried unsuccessfully to block construction of the railroad bridge.

Fifteen days after the bridge’s gala opening, the steamboat Effie Afton struck one of its piers. A stove on the boat overturned, and the Effie Afton burned to the waterline. The bridge caught fire and suffered extensive damage. News of the bridge fire prompted riverboats all along the Mississippi to ring bells and blow whistles in celebration.

The owners of the steamboat sued the railroad company that built the bridge, saying it was a hazard to navigation and should be dismantled. The lawsuit, Hurd et al. v. the Rock Island Railroad, would be a crucial test of the powers of the established river traffic forces and of the upstart railroads. Noted Springfield lawyer Abraham Lincoln had experience working for both sides, but in this case he was one of several attorneys hired by Norman Judd for the railroad companies.

According to a long-accepted but probably apocryphal story, Lincoln traveled to the bridge site to get the facts firsthand. He supposedly walked out on the repaired bridge and met a boy from Davenport who turned out to be the son of the resident engineer on the project. Lincoln and the boy are said to have timed a floating log to calculate the speed of the current. While this story was probably ginned up by the Chicago Rock Island and Pacific Railroad for a 1922 history, there is no doubt that Lincoln by some means familiarized himself with details like the dimensions of the bridge, the angle of the piers, the curve of the river and the depth of the channel.

The trial took place in Chicago in September of 1857. Lincoln was not the lead attorney for the railroad, but he handled the defense team’s summation. He displayed an impressive mastery of the pertinent data, and was able to demonstrate that the accident occurred not because the bridge was a hazard but because the Effie Afton’s starboard paddle wheel failed. He also stressed the vital importance of allowing railroads to span the Mississippi. He said that east-to-west travel was “growing larger and larger, building up new countries with a rapidity never before seen in the history of the world.”

Incidentally, several prominent citizens of Rock Island and Moline who had witness float tests were called as witnesses at the trial, including Moline plow manufacturer John Deere. The 55-year-old Deere testified that he did not see a cross-current affecting the draw under the bridge, but under cross-examination he admitted that he had no knowledge of river navigation.

The trial resulted in a hung jury, which allowed the bridge to stand. Further litigation reinforced this result. (We will examine a separate suit filed on the issue in the story of ANOTHER Iowa connection.) The decision helped to hasten the end of the riverboat era and quickened the pace of expansion and economic growth in the trans-Mississippi West, particularly in Iowa. From his earliest days in politics Lincoln had championed internal improvements, by water and rail, and he pushed for new railroads in both his professional and political careers.

The current Government Bridge in the Quad Cities is near the site of the original bridge. Completed in 1896, it is the fourth to cross what is now Arsenal Island from Rock Island to Davenport.

-

Abraham Lincoln and the Hawkeye State: Lincoln and Ann Rutledge

In these articles about Lincoln, I’ve done my best to adhere to documented facts, which is often hard to do with a historical figure who has achieved legendary status. I beg forgiveness for the arid prose that sometimes results, and in an effort to make it up to you, this month we will explore a chapter of the Lincoln story that carries with it strong colorings of myth, controversy, and romance. And I promise to include an Iowa connection.

Lincoln’s love affair with Ann Rutledge may be the most famous romance that never happened, or it may be a true story whose tragic outcome Lincoln justifiably hoped would remain a private sorrow. Around 1832, Ann was betrothed to a New Yorker calling himself John McNamar, whose visit home that year to assist his family became indefinitely prolonged. Ann waited in vain three years for his return. Meanwhile, young Abe Lincoln came to board for a time at her father’s house. Lincoln was gawky and uncomfortable in the company of eligible females, but he was also a great favorite of women who came to know him in relaxed circumstances, and besides, Ann wasn’t technically eligible, was she?

The Rutledges moved from New Salem to nearby Sand Ridge, but Lincoln, by now a local postmaster, surveyor and first-term legislator, continued to visit. Various witnesses claim he was paying court to Ann, and some believe that they made an agreement to marry once McNamar finally showed himself so Ann could break their engagement. However, in the summer of 1835, Ann became ill with typhoid. Lincoln visited her alone during her illness and left much distressed. After she died on August 25, Lincoln sank into a depression so profound that his friends maintained a suicide vigil. Ann was 22, Lincoln 26.

This story is one of a long list of tragedies that Lincoln had to overcome in his life, but it is one that only came to light after his death, which succeeded Ann’s by thirty years. And the reputation of the man who first spread the tale doomed it to skepticism and outright scorn by many historians.

William Herndon, nine years Lincoln’s junior, became Abe’s law partner in 1844, and their practice wasn’t dissolved until Lincoln’s death in 1865. After the assassination, Herndon was obsessed with the idea of telling the true story of the martyr that he knew so well as a man. He began gathering information from Lincoln’s friends for a biography that he finally finished in collaboration with another writer in 1889.

While long a Lincoln associate, Herndon was not a favorite of Lincoln’s wife. When the sophisticated Mary Todd first came to Springfield, Illinois in 1837, she met the frontier-bred Herndon at a social. Impressed with his dance partner’s gracefulness, Herndon blurted that she “seemed to glide through the waltz with the ease of a serpent.” You try that sometime. Mary was not impressed, and in time she and Herndon became bitter enemies. Mary and Abe married in 1842, and Billy Herndon, who would see Lincoln daily at their law office, was never welcome in the Lincoln home.

Years later, after getting wind of the touching story of Lincoln and his pre-Mary Todd sweetheart, Herndon tracked down 1830s residents of New Salem and quizzed them on the romance. He pulled his research together in an 1866 lecture. Despite indignant protests from the late president’s wife and eldest son, Herndon published his talk in a small booklet, and soon no biography of Lincoln was complete without this intimate look at the adored leader as a young man.

Later historians, some reacting sympathetically to the traditional portrayal of Mary Todd Lincoln as a hysterical harpy, criticized Herndon for asking leading questions and inventing unwarranted assumptions, such as asserting that Ann died of anguish over being engaged to two swains at once. By the mid-20th century, it became fashionable to deny that anything more than an innocent friendship existed between Abe and Ann.

However, the dispute never completely died down, and there are now serious historians who are willing to overlook Herndon’s excesses and accept the earnestness of his eyewitnesses. You may draw your own conclusions, but I choose to believe that Lincoln captured the heart of the winsome Ann, only to see his darling decline and perish, which affected him so deeply he could not bear to think about the rain falling on her grave.

And so, as Lincoln would have wished, we will draw a veil over this tragic – wait! I almost forgot! The Iowa connection!

The village of New Salem petered out when the adjacent Sangamon River proved ill-suited to navigation. The Rutledge family, minus Ann and her father James, who also succumbed to typhoid later in 1835, moved in 1839 to Iowa. Ann’s mother Mary took her surviving three sons and three daughters to Birmingham in northern Van Buren County. Some of them wound up in Oskaloosa, and some eventually left the state. Robert Rutledge became sheriff of Van Buren County.

Lincoln’s regard for the family remained constant, and he supposedly told an old friend visiting him shortly after his election as president that “I have loved the name of Rutledge to this day.” Evidence of this attachment may be found in the fact that he appointed Bob Rutledge as U.S. Provost Marshal in Iowa’s first congressional district during the Civil War.

Pilgrims still visit Ann Rutledge’s grave near the restored New Salem, but Iowans may find the marker over the mortal remains of her mother at Bethel M.E. Cemetery in Lick Creek Township in Van Buren County. Mary left her spinning wheel to daughter Nancy, who donated it to the Carnegie Historical Museum in Fairfield before she died in 1901. Nancy Rutledge Prewitt, Ann Rutledge’s sister, is buried in Fairfield’s Evergreen Cemetery.

A. Lincoln and Billy Herndon -

Abraham Lincoln and the Hawkeye State: Lincoln’s Iowa Land Holdings

Encouraged by the 20-odd people reading my Abraham Lincoln-related compositions, I am considering what I should write about next. In the meantime, I am going to post some articles I wrote several years ago. First were some articles about Lincoln’s connections to Iowa that I initially wrote for the Iowa County, the monthly magazine of the Iowa State Association of Counties, in 2007-2008. These also appeared in the Winter 2008 edition of Iowa Heritage Illustrated magazine, published by the State Historical Society of Iowa. They were titled as a group “Abraham Lincoln and the Hawkeye State.”

The introduction in Iowa Heritage Illustrated reads as follows:

“To celebrate the bicentennial anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, historians and biographers are writing an astounding number of books and articles about our 16th president. The attention is well deserved: we owe Lincoln the lion’s share of credit for saving the United States from disintegration and ending its abhorrent reliance on slavery.

“But the attraction to Lincoln goes beyond his mighty acts of state. His unaffected nature, his compassion, and his martyr’s death have bestowed a historic charisma upon him that attracts adherents from all lands and eras.

“It is an intensely human reaction to seek to discover what we might have in common with such a beloved figure. Iowans will be pleased to find that Lincoln was connected to Iowa in ways that closely tied him to many aspects of the early history of our state.”

Here follows one version of the first article.

Lincoln’s Iowa Land Holdings

by Grant Veeder

Abraham Lincoln was not a particularly wealthy man. His humble beginnings are well-known, and while he built a respectable law practice, in the 1850s he found himself working so much in political campaigns (his own and others) that he had to concentrate heavily on his profession in alternating years to make up for missed fees.

A salient mark of prosperity, then as now, was real estate. Lincoln owned a house in Springfield, Illinois, and possibly a home during his time in New Salem, but the greater part of the real property he had at the time of his death was parcels of land in the state of Iowa.

The story of Lincoln’s land holdings goes back to the time when he was just embarking upon adulthood. Lincoln had spent his minority engaged in the hard and relentless labor of pioneer farming, sometimes being hired out by his father to neighbors. On the plus side, this contributed to his fabled strength. (He supposedly once lifted a 600-pound chicken coop.) However, it also instilled in Lincoln an antipathy toward physical labor. From an early age, he had a powerful ambition to make a mark in the world through his intellect.

After working for his father until age twenty-two, Lincoln in 1831 settled in the village of New Salem, Illinois, where he had been promised a job in a store. The store hadn’t opened by the time he got there, so initially he worked a variety of odd jobs and got to know his neighbors. A natural storyteller with a knack for self-deprecating wit, Lincoln quickly became popular, and in 1832 he announced for the state legislature. The period between his announcement in March and the election in August proved to be quite eventful, thanks to a Native American tribe located at that time in Iowa.

The Sauk and Fox Indians had lived on both sides of the Upper Mississippi River, but were by this time confined to the Iowa side by treaty. In April of 1832, some of them crossed back into Illinois under the leadership of the warrior Black Hawk. They wanted to return to their former farming settlements along the Rock River, but the white settlers saw the move as a hostile act. The situation soon degenerated into what became known as the Black Hawk War.

After misunderstandings resulted in violence, panic spread across the Illinois prairie, and the governor called for troops. Lincoln enlisted, and embarked upon the unique experience of the early American militiaman. The poor training and discipline of state militias invited the scorn of regular army soldiers, but the U.S. Army before the Civil War was a tiny force. Quick-developing emergencies (Indian uprisings, escaping slaves) had to be met, at least initially, by local volunteers.

The fierce Yankee pride in democracy of our early republic is nowhere better demonstrated than by the long-held tradition of the militia electing its officers. A popular volunteer, like Abe Lincoln, with utterly no military experience, like Abe Lincoln, could be elected captain of his company, just like Abe Lincoln. So Lincoln went off to war at the head of his troop of neighbors from Sangamon County. He said in the late 1850s that his election was “a success which gave me more pleasure than any I have had since.”

Lincoln saw no action, despite re-enlisting twice as a private after his initial month of service expired. “I was out of work,” he later explained. “. . . There being no danger of more fighting, I could do nothing better than enlist again.” In July, with more federal troops on the scene, he was discharged with other militia members as provisions grew scarce during the chase after Black Hawk in northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin. The war ended on August 2 in a slaughter of Sauk and Fox warriors and noncombatants at the Battle of Bad Axe on the Mississippi River.

Back in time for a little campaigning, Lincoln relied more on his personality than a detailed platform. “My politics are short and sweet, like the old woman’s dance,” he quipped from the stump. The top four vote-getters in Sangamon County would win seats in the legislature in the August 6 election. Lincoln ran eighth out of thirteen candidates.

Thus ended Lincoln’s campaigns, military and political, of 1832. His political experience would bear fruit in two years when he ran successfully for the legislature; his military service would result, after a much longer time, in the acquisition of real estate.

Rewarding military veterans with land is a custom going back to ancient times, and such a popular law was easy to pass in the U.S. Congress in the first half of the nineteenth century, as the United States expanded rapidly in territory. Congress had compensated veterans of the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican-American War with land grants, and in 1850, it passed a law doing the same for veterans of any Indian war after 1790. Lincoln received a warrant good for forty acres. He eventually engaged Dubuque attorney John P. Davies to use it to acquire a parcel in Tama County. His title was perfected in 1855, for the following described land: “The Northwest quarter of the Southwest quarter of Section 20 in Township 84 North, Range 15 West.”

In the same year, Congress gave veterans more land. Lincoln was eligible for 160 acres, less any amount already bestowed. Once again, he did not act immediately. Was he waiting to find a juicy plot, hoping to make his fortune on speculation? Not according to a story told by a couple of Iowans.

W.H.M. Pusey was an old friend of Lincoln’s from Springfield who moved to Council Bluffs. He and D.C. Bloomer reminisced about Lincoln’s 1859 visit to their city about forty years after the fact. They recalled him pulling out his warrant, still unused, during a conversation about the old days. They chided him for not turning it to his advantage. He said that he brought it along thinking he might find some land in Kansas or Iowa, but that he had previously just thought he would someday give it to his sons, “that they would always be reminded that their father was a soldier!” There were some glaring inaccuracies in their story, but there is a ring of truth about it.

Ultimately, he took title to his 120 acres in Crawford County. Acting as his own attorney, he got possession in 1860, shortly before his election to the presidency, of the following described parcel: “The East half of the North East quarter and Northwest quarter of the North East quarter of Section Eighteen in Township Eighty four North of Range Thirty nine west.”

One of Lincoln’s purposes for visiting Council Bluffs was to inspect some land locally. His friend, Norman B. Judd, was a railroad attorney who borrowed $2,500 from Lincoln in 1857, at 10% interest per year, to purchase land in Council Bluffs, believing the area was destined for a major railroad. Now Judd wanted to renew and increase the loan, and offered seventeen city lots in Council Bluffs and ten acres along the anticipated route of the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad as collateral. After his trip, Lincoln accepted the terms, and the land was quitclaimed to him.

Lincoln the Land Baron never made it big. After he became president, he knew he might be criticized for starting the western railroad at the town where he owned land, but he did it anyway because it made the most sense. However, he realized nothing from the venture – the property reverted to Judd when the loan was repaid after Lincoln’s death.

Lincoln died without seeing the farmland he acquired in Tama and Crawford Counties. In 1874, his widow, Mary Todd Lincoln, sold the Tama County land to their son Robert for $100. Robert and his wife Mary Harlan Lincoln sold the farm to Adam Brecht of Tama County in 1875 for $500.

After Mary Todd Lincoln’s death in 1882, Robert was the sole surviving heir of his parents, his three brothers all having died before reaching full adulthood. He and his wife sold the Crawford County parcel in 1892 while living in London, where Robert was serving as American minister to Great Britain. Henry Edwards of Crawford County bought the land for $1,300.

There’s a postscript that ties the whole story together: The Fox Indians are also known as the Meskwaki. They were exiled to Kansas after the Black Hawk War, though some never left. In 1857 the Iowa legislature, in unprecedented fashion, allowed some of them to buy land so they could live in Iowa. They purchased land in Tama County, just a few miles from Lincoln’s land, and the tribe lives there to this day.

Below: Markers in Tama and Crawford Counties

-

Grant Veeder’s First Blog Post

As a member of the Iowa Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission during the official term of that celebration (2008-2010) I wrote several presentations and articles, at first involving Lincoln’s connections to the state of Iowa and then branching into other Lincoln-related subjects to satisfy requests or my own inclinations. For a long time my book reading was almost exclusively in Lincoln texts.

Later I settled back into a more normal life, but the January 6, 2021 insurrection reminded me of the siege-like state that Washington, D.C. endured in the opening days of the Civil War, and after brushing up on my sources I told that story on Facebook. Then I told about the assassination plot that Lincoln avoided on his way to his first inauguration, then I wrote an episodic history of the conspirators in the successful assassination attempt four years later.

I wasn’t sure how long of a post that Facebook readers would endure. It turned out they could be pretty long. How patient would the readers be with me as I proceeded with only the vaguest of outlines, researching my often confused recollections as I went along? Some of them were very patient indeed. I had no expectations of readership, and it is impossible for a tech-challenged elder like myself to gauge Facebook interest. I have hundreds of Facebook “friends,” but judging by the responses on the record, there are maybe a few score paying attention to my historical writing. My goal has been to get 20 “likes” for a given post. That looks very pitiful when I actually type it out, but fortunately I greatly enjoy researching and writing the episodes, so a thin stream of encouragement is enough to sustain me.

Near the end of 2021 I finished what I had grandly titled “The Conspirators.” By then I had found out that there are readers who don’t usually reveal themselves online, a comfort. I also found that some readers are very well pleased with my efforts, and that they wanted to see more. At the request of one of them, I wrote a short series on Lincoln and Slavery. This resulted in some very civil disagreements that obliged me to establish my contentions on the firmest possible foundations. I found it a novel way to write a thematic article.

Without a new topic at hand, I thought readers might be interested in some of my previously published material. I have just posted my first “Lincoln and Iowa” article and it gathered nearly 70 likes in a day. This is the sort of attention that I typically get only if I post a dramatic sunset or somesuch. I am consequently starting to take more seriously those kind auditors who suggest that I expose my compositions in a more traditional way. Publishing a book may be an achievable goal, but I have found that creating a blog is much much much much easier. An old college buddy, blogger Laura Cerny, showed me how easy it is, so we’re going to start with a blog.

It is very late, but maybe tomorrow I will post a Lincoln article, and see if I can figure out just how this works. I know I said that it’s easy but I wouldn’t have gotten even this far without the aid of my son Ryan. So don’t expect any frills.

-

Hello World!

Welcome to WordPress! This is your first post. Edit or delete it to take the first step in your blogging journey.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.