Lincoln’s legal practice saw steady growth, while his political career advanced by fits and starts. After an unsuccessful run for one of Illinois’s U.S. Senate seats in 1854-55, he stood for the other in 1858. In October of that year he went to Burlington, Iowa to give a speech. There may not have been many voters in Burlington who could help him, but he had a number of reasons to make such a visit.

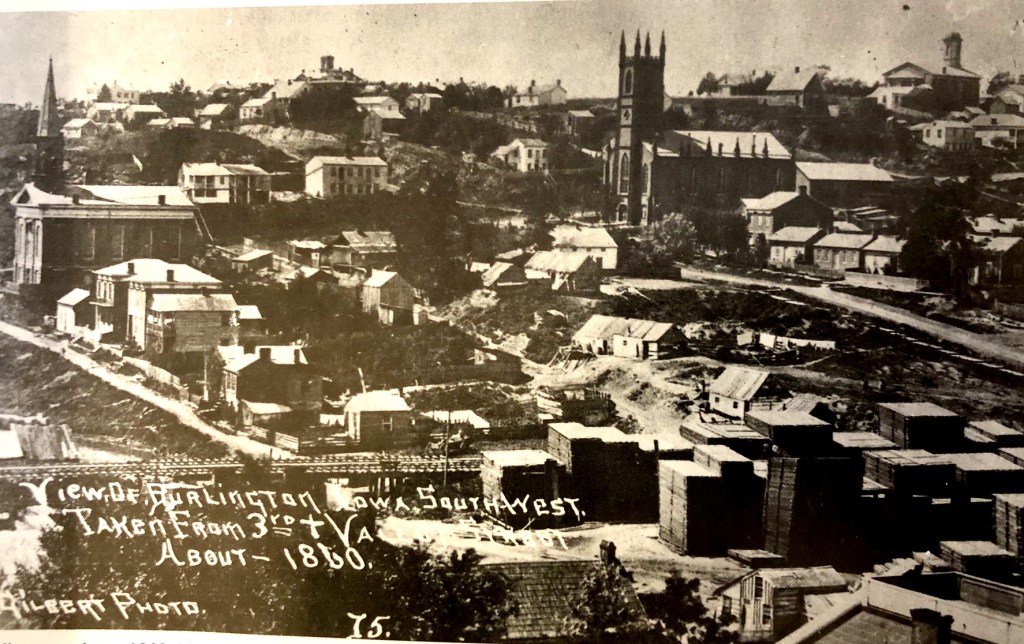

One reason was the doggedness of Burlington residents over the years in inviting Lincoln to come. He had turned down invitations in 1844, 1856 and 1857 that we know of. Burlington was a small settlement at the time, but it had served as the second capital of the Wisconsin Territory in 1837 and was from 1838 to1840 the capital of the Iowa Territory after it separated from Wisconsin. Thus, it was an important political center in the state, and it was the home of James W. Grimes. A member of the first territorial legislature at Burlington who was elected governor in 1854, Grimes authored at least two of the requests for Lincoln visits.

Lincoln explained his disinclination to visit in 1856 in his reply to Grimes: “1. I can hardly spare the time. 2. I am superstitious. I have scarcely known a party preceding an election to call in help from the neighboring States, but they lost the State.”

When Grimes invited him again in 1857, Lincoln wrote that he was very anxious for Republican success in Iowa’s 1858 congressional elections but “I lost nearly all the working-part of last year, giving my time to the canvass; and I am altogether too poor to lose two years together.”

When 1858 came around, Lincoln was trying to fulfill his life dream of election to the U.S. Senate. His opponent was the Democratic incumbent, Stephen A. Douglas, whose Kansas-Nebraska Bill of 1854, which gave new states the right to vote on allowing human bondage, had electrified the slavery issue and brought Lincoln out of self-imposed political exile.

Lincoln proposed a series of debates, and Douglas agreed to hold seven. The fifth was scheduled for October 7 in Galesburg, about 46 miles east of Burlington. They would follow that debate with one down the Mississippi River in Quincy on October 13. Des Moines County Republican Chairman Charles Darwin reasoned that Burlington wouldn’t be out of Lincoln’s way, so he sent him an invitation to speak.

(You probably didn’t mistake Burlington’s Charles Darwin for the British evolutionist of the same name, but this coincidence gives us a chance to note another coincidence: The evolutionist Darwin and Lincoln share the same birthday, February 12, 1809.)

Another factor influenced Lincoln’s acceptance of Darwin’s request. Part of Lincoln’s electoral strategy was to speak in a town after Douglas had spoken there so that he could answer Douglas’s points, and Douglas had already agreed to talk in Burlington. Consequently, after a 1 pm speech in Oquawka, Illinois on Saturday, October 9, Lincoln immediately embarked on the Rock Island packet to sail twenty miles downriver to address an Iowa crowd in Burlington that evening. The staunchly Republican Burlington Hawk-Eye had given details of the impending visit in its October 8th edition, and wound up by saying of Lincoln, “He says he has got so used to speaking that it don’t hurt him a bit and he will talk as long as we want to hear him! HUZZA FOR LINCOLN!”

On his arrival, Lincoln checked in at the Barrett House to freshen up before his speech. Years later, eyewitnesses at the hotel recalled instances of Lincoln’s simplicity. On arrival, he handed the clerk a small packet wrapped in newspaper and said, “Please take good care of that. It is my boiled shirt. I will need it this afternoon.” Apparently it was the sum total of his luggage.

Later, the editor of the Hawk-Eye saw him putting the shirt on. Clark Dunham said that Lincoln came down the stairs to meet a local delegation with his arms stretched high as he struggled to pull his white shirt over his head. He finished tucking his shirttails into his trousers just as he reached the group.

What Dunham did after meeting Lincoln at the hotel is something of a mystery, because his October 11 newspaper reporting on the speech stated, “We regret exceedingly that it is not in our power to report his speech in full this morning.” No transcript of the oration has yet been uncovered. The Hawk-Eye was somehow able to describe the speech as “a logical discourse, replete with sound argument, clear, concise and vigorous, earnest, impassioned and eloquent.” It estimated the crowd at “twelve to fifteen hundred ladies and gentlemen.” Lincoln spoke for two hours, and it apparently “didn’t hurt him a bit”: the newspaper reported (perhaps with a touch of bias) that Lincoln “appeared Saturday evening fresh and vigorous, there was nothing in his voice, manner or appearance to show the arduous labors of the last two months.” This in contrast to Douglas, “whose voice is cracked and husky, temper soured and general appearance denoting exhaustion.”

The speech was given at Grimes House, a hall owned by Governor Grimes. After spending the night at the Barrett House, Lincoln visited Grimes at his home on Sunday before leaving town. Presumably, Lincoln devoted at least a portion of his Saturday speech to politicking for Grimes, who, like Lincoln, was running for the Senate. Unlike Lincoln, he was successful.

The loss was disappointing to Lincoln, but Grime’s biographer, William Salter, who heard both Lincoln and Douglas speak in Burlington, put it in perspective. “Had Mr. Lincoln been elected senator,” he wrote, “in all probability he would never have become President.” And his visit to Burlington would likely have been forgotten.