by Grant Veeder

Lincoln was a natural public speaker whose abilities to clearly explain difficult concepts and to emotionally sway his listeners formed a strong underpinning to his successful legal career. The wide respect for his reputation led to his involvement in a lawsuit that had a dramatic effect on Iowa’s early growth.

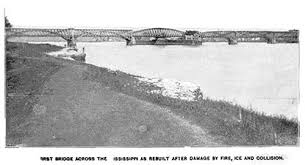

The first bridge across the Mississippi River, three years in the building and completed in 1856, connected Rock Island, Illinois and Davenport, Iowa, and was a major breakthrough for western travel and commerce. Riverboat operators previously had a monopoly on the large-scale movement of passengers and goods, and had tried unsuccessfully to block construction of the railroad bridge.

Fifteen days after the bridge’s gala opening, the steamboat Effie Afton struck one of its piers. A stove on the boat overturned, and the Effie Afton burned to the waterline. The bridge caught fire and suffered extensive damage. News of the bridge fire prompted riverboats all along the Mississippi to ring bells and blow whistles in celebration.

The owners of the steamboat sued the railroad company that built the bridge, saying it was a hazard to navigation and should be dismantled. The lawsuit, Hurd et al. v. the Rock Island Railroad, would be a crucial test of the powers of the established river traffic forces and of the upstart railroads. Noted Springfield lawyer Abraham Lincoln had experience working for both sides, but in this case he was one of several attorneys hired by Norman Judd for the railroad companies.

According to a long-accepted but probably apocryphal story, Lincoln traveled to the bridge site to get the facts firsthand. He supposedly walked out on the repaired bridge and met a boy from Davenport who turned out to be the son of the resident engineer on the project. Lincoln and the boy are said to have timed a floating log to calculate the speed of the current. While this story was probably ginned up by the Chicago Rock Island and Pacific Railroad for a 1922 history, there is no doubt that Lincoln by some means familiarized himself with details like the dimensions of the bridge, the angle of the piers, the curve of the river and the depth of the channel.

The trial took place in Chicago in September of 1857. Lincoln was not the lead attorney for the railroad, but he handled the defense team’s summation. He displayed an impressive mastery of the pertinent data, and was able to demonstrate that the accident occurred not because the bridge was a hazard but because the Effie Afton’s starboard paddle wheel failed. He also stressed the vital importance of allowing railroads to span the Mississippi. He said that east-to-west travel was “growing larger and larger, building up new countries with a rapidity never before seen in the history of the world.”

Incidentally, several prominent citizens of Rock Island and Moline who had witness float tests were called as witnesses at the trial, including Moline plow manufacturer John Deere. The 55-year-old Deere testified that he did not see a cross-current affecting the draw under the bridge, but under cross-examination he admitted that he had no knowledge of river navigation.

The trial resulted in a hung jury, which allowed the bridge to stand. Further litigation reinforced this result. (We will examine a separate suit filed on the issue in the story of ANOTHER Iowa connection.) The decision helped to hasten the end of the riverboat era and quickened the pace of expansion and economic growth in the trans-Mississippi West, particularly in Iowa. From his earliest days in politics Lincoln had championed internal improvements, by water and rail, and he pushed for new railroads in both his professional and political careers.

The current Government Bridge in the Quad Cities is near the site of the original bridge. Completed in 1896, it is the fourth to cross what is now Arsenal Island from Rock Island to Davenport.